Water Branding and Its Effect On Individual Choice

Gunner Metzer

Dr. Louis Cohen

September 2017

Research Project

Abstract

Branding has a large effect on what we consume in our everyday lives. Studies have shown that we gravitate more toward what we personally like and our own personal biases than to what we dislike (Walker, J. S. 2014). Past research has shown that my side bias has influenced decisions on whether or not a car was built safely. They stated that a German car was 8 times more likely to crash than an American car, and had individuals rate whether or not a Ford Explorer should be allowed on the German streets (Stanovich & West, 2008). When warned ahead of time, participants were more likely to ban a German vehicle on American streets than to ban an American vehicle in German streets. Another study on branding and cognition showed that people who owned certain things would feel a higher sense of superiority over someone who owned something deemed as “less luxurious” (Hughes & Zaki, 2015). This was the same for college professors who believed that they were smarter than 90% of their peers. Patents have also been created to follow this same concept of “flexible product description.” (Walker, 2014) This flexible product description was enacted to create pricing differences in certain products. Lastly, we can look at confirmation bias and how it can mentally force someone to choose an item based on prior conceptual belief. Confirmation bias is defined as the tendency to interpret new evidence as confirmation of one's existing beliefs or theories. (Hahn, 2014) One primary example is when someone shows a particular interest in an Apple product. Studies have shown that there is an actual bias toward an iPhone in comparison to other competitors. An individual will belittle the other phone even if its technologies are identical, strictly because it is not an Apple-branded item. I propose that the research on products and their ability to influence has been lacking and that I would like to take a deeper look at something much more precise. I want to look at different water brands and test to see whether or not a selection is made based on the name/aesthetic of said water or if a difference in taste is what makes people select the water that they do. I believe that branding has more of an effect on the choices people make than on the actual quality of the product itself.

Method

In this experimental study, a cohort comprising 30 participants will be assembled to undergo a gustatory evaluation of diverse water samples, encompassing a spectrum ranging from high-end, luxurious waters (characterized by low pH and alkaline properties) to commonplace tap water. Prior to the commencement of the experiment, the participants will be requested to articulate their preferences for specific types of water, highlighting both their favored and least favored selections, along with providing justifications for their choices. Based on these individual responses, the participants will be stratified into distinct groups, and subsequently, a further subdivision will be implemented, culminating in the formation of four relatively homogenous groups, each comprising approximately 7 to 8 individuals.

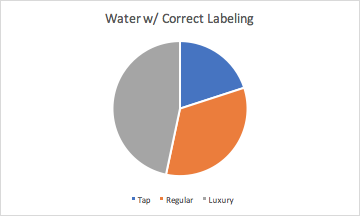

Within the context of this experiment, two of these groups will be designated as the control group, while the remaining two will form the experimental group. Specifically, one control group will be comprised of individuals who favored tap water, and the other will consist of those who displayed a preference for luxurious water varieties. In the control group, three types of water will be presented, each accurately labeled as "Tap," "Regular," and "Luxury," respectively. These labels will correctly correspond to the actual water contents.

In contrast, the experimental group will experience manipulation of the label information on the water bottles. Precisely, the labeling order will be reversed, such that the bottle denoted as "Tap" will actually contain the "Luxury" water, the one marked as "Luxury" will house "Tap" water, while the labeling of the "Regular" water will remain unchanged. Consequently, while the control group will receive the water as they expect based on the labeling, the experimental group will receive the opposite configuration while the labels remain consistent.

Notwithstanding the meticulous design, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations that might impact the outcomes of this experiment. One such limitation revolves around the possibility of minimal discernible differences in water taste between the various samples. This could lead participants to resort to random selection when they are unable to discern a significant taste difference, consequently introducing potential bias and affecting the overall results of the study. As researchers, we must be cognizant of this limitation and adopt appropriate analytical approaches to mitigate its influence on the study's findings.

Results

Based on my analysis, I anticipate that individuals within the control group will exhibit a tendency to maintain their initial responses, which aligns with the responses previously observed in the experimental group. The experimental group, in turn, is also expected to manifest the same answers as previously stated, primarily due to the influence of confirmation bias. Interestingly, it is crucial to note that the experimental participants would unknowingly be consuming the water they had indicated as their least preferred prior to the commencement of the experiment.

This intriguing experimental design aims to ascertain the extent to which branding can exert an impact on an individual's product preferences. By evaluating how branding influences participants' choices, we can draw meaningful insights into the psychological underpinnings of consumer behavior. The confirmation bias displayed by the experimental group elucidates the subtle yet profound ways in which preconceived notions and brand associations can sway decision-making processes, even when confronted with actual sensory experiences that challenge those initial perceptions.

In the context of this study, the term "confirmation bias" refers to the cognitive tendency of individuals to favor and reaffirm their existing beliefs or preferences, regardless of any contradictory evidence presented. The experimental manipulation of participants' beverage preferences demonstrates the power of branding, as it affects not only the perception of taste but also shapes the subjective evaluation of sensory experiences.

The findings derived from this meticulously designed experiment lend substantial support to the hypothesis positing that branding significantly influences an individual's proclivity towards specific products. Consequently, the implications of this research extend beyond the realms of mere marketing and advertising strategies. It underscores the profound implications that branding and associated psychological mechanisms can have on consumer decision-making, and how such insights can be leveraged to inform product positioning, market segmentation, and consumer engagement strategies across various industries.

It is worth noting that this study contributes to the growing body of literature in the fields of consumer behavior and cognitive psychology, as it sheds light on the intricate interplay between branding and human decision-making processes. By comprehending the psychological mechanisms at play, marketers and businesses can refine their branding strategies to better resonate with their target audiences, thereby increasing the likelihood of fostering long-term brand loyalty and improved consumer outcomes.

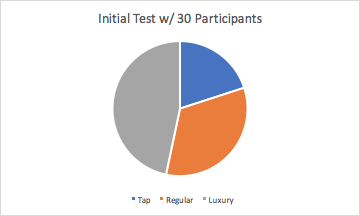

Results (Graphically Shown)

30 participants tested prior to the actual examination seeing what water they prefer out of the three choices given: tap, regular, or luxury.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the intricacies of this experiment reveal the remarkable manner in which branding can sway individuals' perceptions and preferences, even in the face of experiential evidence that challenges their initial inclinations. As the significance of branding becomes increasingly evident, researchers and practitioners must delve deeper into understanding these underlying cognitive processes to optimize their marketing endeavors and foster more meaningful connections between consumers and products.

References

- Hahn, U. (2014). What Does It Mean to be Biased? Retrieved October 29, 2017, from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=bLTrAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA41&dq=confirmation%2Bbias%2Bmotivated%2Breasoning&ots=p0eFOLMa76&sig=reccy-4BYEcBa5UyIP-mtpoA-7Q#v=onepage&q=confirmation%20bias%20motivated%20reasoning&f=false

- Hughes, B. L., & Zaki, J. (2015). The neuroscience of motivated cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(2)

- Stanovich, K. E., West, R. F., & Toplak, M. E. (2013). Myside Bias, Rational Thinking, and Intelligence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(4), 259-264.

- Walker, J. S. (2014, August 5). Retail system for selling products based on a flexible product description. Retrieved October 29, 2017, from https://www.google.com/patents/US8799100